The Stranger: Life’s Meaning on Trial

Albert Camus’ The Stranger is a gut-check. A quiet slap. A cigarette flicked in the face of every polite illusion you’ve ever clung to. Love? Meaning? God? All on the chopping block. And the executioner? A sunburned, emotionally unavailable Frenchman who probably wouldn’t flinch if you told him his dog died. This is a story you metabolize. You come out the other side disoriented, like waking up from a nap where you dreamt you were both the judge and the condemned. It’s the literary equivalent of sitting in traffic for three hours, questioning your career, marriage, beliefs, and then realizing you forgot to turn the stove off.

How I Found The Book

I found it in a hotel lobby, waiting for a blind date who ghosted me like it was her spiritual calling. There it was, staring at me from the coffee table like it knew I was already halfway to nihilism. I picked it up. Thirty minutes in, I was hooked. By the end of chapter one, I was haunted. My date never showed, but Camus did. And he hasn’t left. That moment changed something. I walked out into the parking lot, not disappointed but reborn. Lonely, but with new vocabulary for my loneliness.

Meursault: Patron Saint of "I Don’t Give a Damn"

Here’s the thing: Meursault isn’t a psychopath. He’s a mirror. Cold, cracked, and held way too close to your face. When his mother dies, he doesn’t cry. When Marie asks if he loves her, he says no, but not in a cruel way. He did it in an honest way. His honesty doesn’t protect him. It damns him. Because people can stomach murder more easily than they can stomach someone who doesn’t perform grief. Meursault is allergic to pretense. In a world obsessed with performance, that makes him public enemy number one. His crime isn’t the bullet; it’s the refusal to kneel before society’s unspoken script.

The Beach, the Bullet, and the Sun That Judges All

That infamous beach scene is a metaphysical panic attack. The sun is blistering, the light too real. Meursault doesn’t plan it. He walks into that moment like we’d walk into heartbreak: dazed, vulnerable, unarmed by logic. And then: five shots. No motive. No build-up. Just a flash of absurd clarity and collapse. Camus writes it like a man describing a dream he barely remembers. No rage. No revenge. Just a moment where heat becomes action, and we’re left holding the silence.

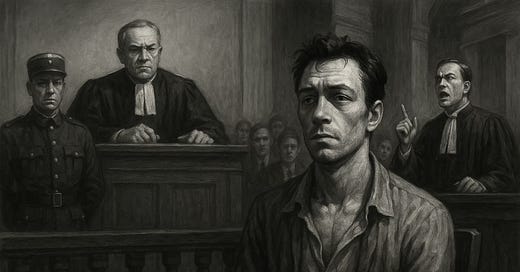

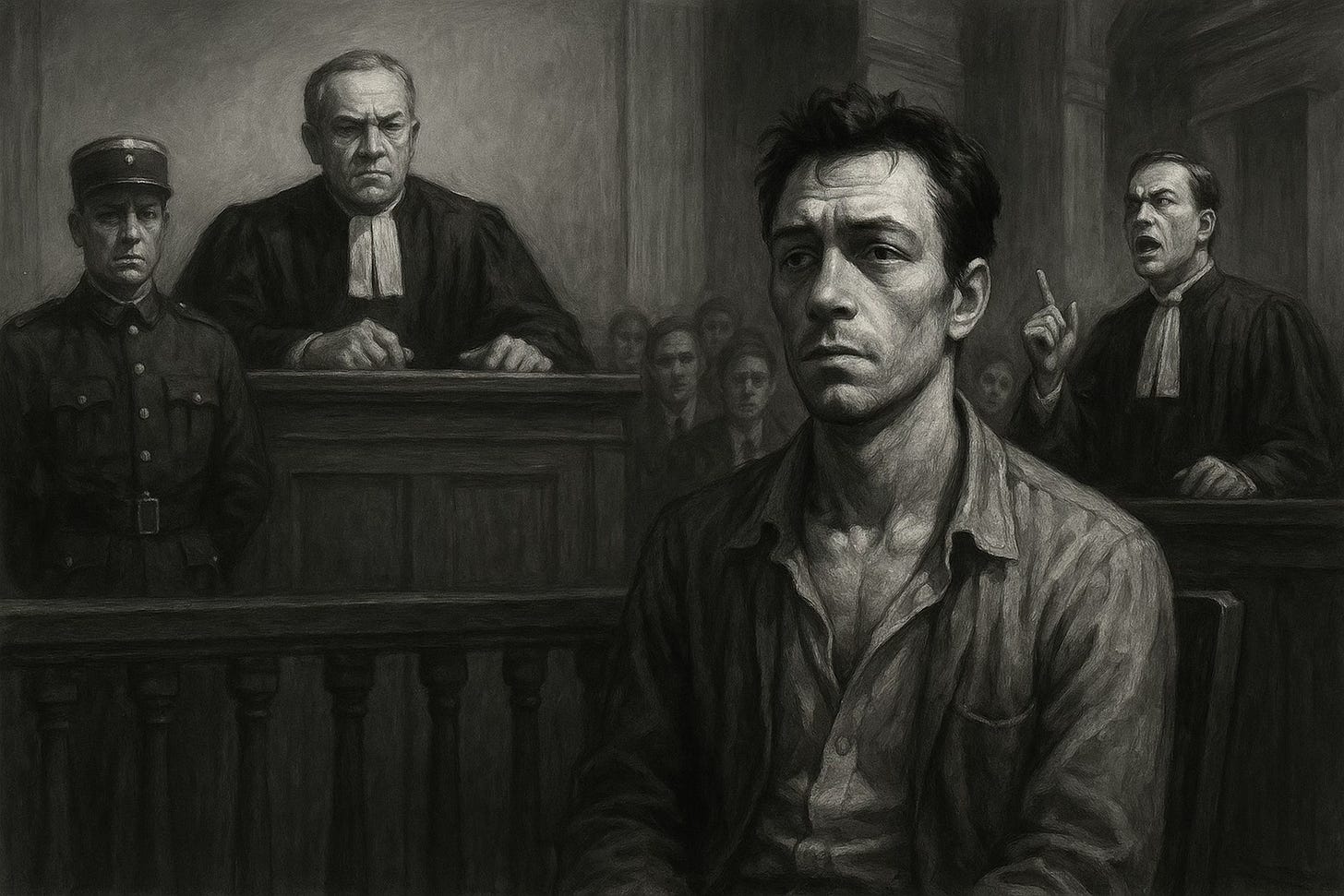

The Trial: The Theater of the Absurd

The book's second half plays out like Kafka’s The Trial, but with better lighting. Meursault is put on trial not for killing a man, but for failing to cry. The courtroom becomes a stage, and he’s cast as the villain simply because he won’t act the way they want him to. He won’t say sorry. He won’t beg. He won’t lie.

He’s condemned for being too honest. Too indifferent. Too real.

The prosecutor isn’t building a case. He’s telling a bedtime story to adults who need the world to make sense. But Camus rips the blanket off. He exposes the trial as a performance, and society as a machine that grinds down whatever doesn’t play along.

The Cell, the Chaplain, and the Final Refusal

While Meursault waits for death, there’s no redemption arc. No come-to-Jesus moment. A chaplain visits him like some divine salesman offering comfort. Meursault tells him to kick rocks. This is one of the most beautiful acts of defiance in literature. Calm. Absolute. He doesn’t need belief to make peace. He doesn’t invent meaning to soften the blade. He accepts the absurd. And in doing so, he transcends it. Freedom, Camus tells us, doesn’t come from belief. It comes from clarity. When you finally stop lying to yourself, even death loses its teeth.

How Camus Built the Stranger

Camus was born into poverty in French Algeria. He grew up under that same sun that haunts the novel. He knew what it was to be insignificant, to sweat through grief, to laugh without hope. The Stranger is soaked in that landscape, where light is too sharp to romanticize. He wrote the novel in the 1940s, while Europe was losing its mind and choosing sides. He paired it with The Myth of Sisyphus, where he explains absurdism, the idea that humans desperately seek meaning in a universe that offers none. In The Stranger, Camus makes us feel it. Every page is an emotional shrug wrapped in sunlight. Every line asks: What if the world doesn’t care? What if it never did?

Why It Still Cuts So Deep

Because deep down, we know it’s true.

We build lives around rituals. We say "I love you" like it’s armor. We plan for futures we can’t control. And Camus, through Meursault, burns it down, not out of malice, but out of mercy. He wants us to stop pretending. The Stranger is a book that haunts you, not with horror, but with honesty. It stays in your bones. It lingers in elevators, long drives, and late-night silences. It teaches you to stop reaching for comfort and start reaching for truth, even if it’s cold.

The final question is this: Are you brave enough to live like him? Admit that most of what we say, do, and feel is performance. That love isn’t always profound. That grief doesn’t always show up on cue. That death is the only certainty, and still—still—we can find peace. That’s Camus’s final gift: not hope, but lucidity. A flashlight in a meaningless hallway. A voice that says, You don’t have to pretend anymore.

(If you enjoy this review, consider giving a donation; I’m sure Meursault wouldn’t do it. Thank God he’s not real.)